Not a lot of the city of Euromos is currently above ground but the temple is and it is very good indeed.

Two of the sides of the temple are standing

as is part of the doorway to the inner sanctum.

which is quite well preserved.

There are even a few columns remaining from a third side.

The site of the Altar is to one side of the temple

and there are plenty of remains and evidence of excavation around the rest of the site.

Some of the pillars are partly finished (as in the above photograph) and some are completely finished as in the picture below. Obviously money was a problem here as in other sites.

Interestingly, many of the pillars have  plaques carved into them upon which is an inscription detailing who paid for the pillar. Each of these three has an inscription in the middle, as do many of the others including one lying on the floor.

plaques carved into them upon which is an inscription detailing who paid for the pillar. Each of these three has an inscription in the middle, as do many of the others including one lying on the floor.

An inscription says “Menecrates, a physician and magistrate donated five of the 30 columns of this temple and Leo Quintus, a magistrate donated another seven”

On the rear side of the temple there is a small symbol on the stone. It protrudes from the stone rather than is excised into it

which is a far hard thing to do. It looks like two ears and an axe or maybe a bird and something? Its purpose / symbolism is not known but the double headed axe was a symbol related to the patron god of stonemasons and a double headed axe and a pair of ears have been found else where dedicated to Apollo Carios.

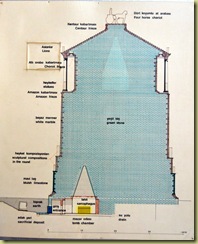

In the nearby town of Milas (ancient Mylasa) is the Gumuskesen (Silver Purse) tomb built in the first century AD. It is said that it bears some resemblance to the tomb of Mausolosin nearby Bodrum (or would have done had that tomb not been demolished in 1745).

is the Gumuskesen (Silver Purse) tomb built in the first century AD. It is said that it bears some resemblance to the tomb of Mausolosin nearby Bodrum (or would have done had that tomb not been demolished in 1745).

One can see through a gate into the inside where the sarcophagi would have been left

and the interior of the roof is in good condition and shows fine carvings. The mausoleum in in the middle of a beautiful modern day park.

Having briefly stopped for lunch under an 800 year old tree,

Stratonikeia awaits us as thunder reverberates around the mountains.

It is interesting for numerous reasons. It dates from maybe around 300BC or earlier, it became Roman in 167BC and had a difficult relationship with Rome for many years.

The ancient city lives side-by-side with the old Turkish village of Eskihisar which is mainly in ruins and nearly empty (bar the five people said to be living there when we explored). The whole area is devoted to opencast mining and it was said that an earthquake in the 1950s led to an attempt to empty the village so that the area could be mined. Then the full nature of the ancient city was discovered and the site was saved.

Hence there is a 19Cth Mosque on the edge of the site,

and old houses cheek by jowl with ancient remains

some of which look almost as old as the buildings which would date two millennia before them.

On the way to the theatre, we walked past a

site undergoing excavation.

The building contains a number of shops, this one is possibly a paint shop or an olive oil / wine shop there being the remains of two large amphorae embedded in concrete.

Underneath the site lay numerous underground pipes – this area is still work very much in progress and therefore there will be a lot of finds yet to come.

The Theatre (seating around 15,000) is built into the hillside and whilst it is unremarkable, it is easily redeemed by a number of items.

On a stone near the theatre stage is a carving of a Thyrsos which is a giant fennel topped by a pine cone – it has a religious role in ceremonies devoted to Dionysus.

There are blocks of stone with carved inscriptions on them

about 2/3rds of the original seating remains

and one section clearly shows the ripple of an earthquake wave passing through the theatre.

and one section clearly shows the ripple of an earthquake wave passing through the theatre.

Like many other buildings, the Bouleterion

sits adjacent to more modern buildings

and is typical of its type and also has the usual games carved into the floor.

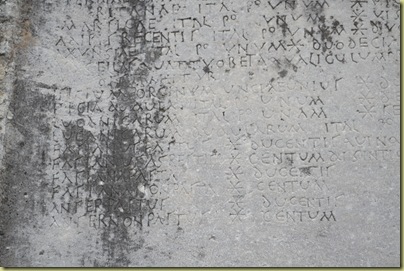

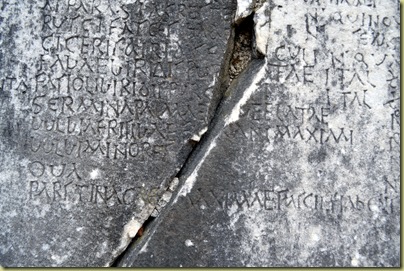

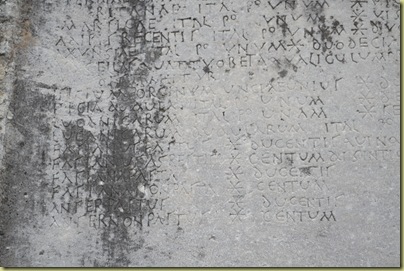

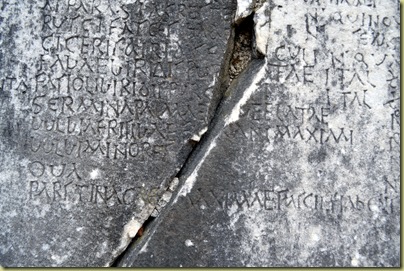

And then you walk around the corner and see the carved writing on the side wall

and you have come across an original copy of the Diocletian Price Code dated AD301.

Around the end of the second century AD, Emperor Gaius Aurelis Valerius Diocletianus Augustus decided that he could solve the problem of inflation by dictating what every item should cost throughout the empire. On penalty of death, everyone would have to sell at no more than the official price and buy at no more than the official price. So illiterate stone masons were sent out across the empire to carve the price code in Latin onto town hall walls (hence the spelling mistakes). However the townspeople were largely illiterate and many of those that could read would do so in Greek – it was a spectacular failure.

Reading the price code on these walls, you can just about work out what the prices of certain items were. For examples, Five of the best cauliflowers cost 4 denarii, the same price as ten second best cauliflowers.

A detailed treatise on the Price Code can be found here (in Latin and translated!)

The Colonnaded Street

The Colonnaded Street is a good example of

how a street close to a city gate worked and what would have been in it. Like much of the site, it is under excavation.

how a street close to a city gate worked and what would have been in it. Like much of the site, it is under excavation.

The excavations have uncovered exampled the crude reuse of sections of

original building material at a later date,

and the city sewer running just beneath the surface of the street

and the city sewer running just beneath the surface of the street

At the city gates end (only one of them is still standing), there is a fountain originally positioned between the two gates and which would have been fed by an incoming aqueduct.

Because of the fountain, this is a place with numerous water pipes and other water related features including

water pipes in the corner walls,

a stone elbow joint

another stone elbow joint but this time with the original earthenware pipes in it

a complicated arrangement showing an earthenware pipe inside of a marble column (perhaps) with an elbow joint at the end,

a number of pipes spreading away underground from the fountain, presumably to feed other areas of the city,

and a piece of the stone wall around the fountain which shows a groove cut in it

possibly cause by the wear and tear of ropes hauling out buckets of water from the fountain.

Unusually, there is the remains of a mausoleum inside the city walls – for this to be the case, the person inside had to have been very important and classified as a hero.

Outside of the city gates is the city Mausoleum,

Outside of the city gates is the city Mausoleum,

with a fine example of a tomb

the door still lying where it was cast aside by grave robbers and the inside showing the resultant empty disarray.

The Gymnasium

At 180 metres long, the Gymnasium complex

is the longest known in Antiquity.

Built around 175BC, it contained a number of

exercise rooms

and a semi circular classroom.

Some of the walls show evidence of having been rebuilt following earthquake damage.

The building also showed us for the first time on this trip, false semi-circular columns shaped into the ordinary stonework of the walls.

And tucked away in a corner lying forgotten and unnoticed is the base of a fountain with the drainage channel clearly evident.

Although rarely visited, the site is likely to be added to the UNESCO list of important historical sites in the near future.