As a means to getting us thinking the right archaeological way, our first day involves a visit to two sites some distance to the south – Heraion and Paestum which together essentially form the Greek colony of Poseidonia.

The Heraion (Temple of Hera Argiva) was built by Greek colonists at the mouth of the Sele river.

The site (free entry) appears to the casual visitor as a large field with some obvious foundation stones at various places in the field.

These are the foundations of the ancient Greek Doric Temple which was constructed around 500 BC. It measured 19 metres by 39 metres and had 8 by 17 columns. The temple was damaged by fire around 400 to 350 BC and then restored. The sanctuary survived until the 2nd Century BC. Much of the stone work was reused in local houses of the time and some is still below ground.

There were also two sacrificial altars there at which 200 cattle at a time might meet their end.

We are seeing this site, partly so we can get a feel for the shape of buildings (and the start of a process of learning how to “read the site”) but also to provide a context for some metopes which we are to see later in the day which come from the site.

A few miles away is Paestum (pronounced either “Piestum” or “Peestum” depending on which version of Latin pronunciation you subscribe to) which is an ancient Greco-Roman city. Settled by Greek colonists in the 6th century BC, it was later occupied by Lucanians, Romans and Christians.

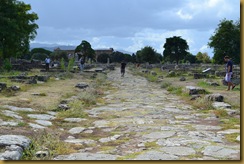

It is a large site (fee for entry), the main entrance to which is at the top of the map. As is common on many sites in Italy, housing has been built over the top of part of it (not always in ignorance of what is beneath) and between 1827-29, significant damage to the site was caused by the construction of part of the Lower Tyrrhenian Road (also known as the Calabrian Road). This road can be seen running top to bottom on the above map, a little to the right of centre (straight through the amphitheatre).

Roman towns usually are bisected by two roads, the E.-W. decumanus maximus and the N.-S. cardo maximus (shown above), dividing the city into four parts, and the Forum, which was the political, social and religious centre of the city, was located near the compitum, the intersection of the two main roads.

We are focusing on the three temples, a few houses and other some other buildings of importance to the town.

Dominating the entrance area is the Temple of Hera, a lot of which is still standing and it is an impressive building. As is often the case, a temple built for one religion becomes a temple of another and this temple became a Christian basilica by around the 5thC AD.

The diagram above labels the various parts of traditional temples

and here you can see the slots between the Trglyphs which were originally in filled with

carved Metopes such as those below which picture

various scenes from historical stories such as (above) Hercules killing the Giant Alcyoneus (his 10th labour)

or Sisyphus attempting to roll a ball uphill but permanently destined to have it roll down again. There are numerous other metopes in the museum adjacent to the site.

Around the top of the temple were Lion shaped gargoyles

and nicely carved freezes.

There are two other temples on the site, this one is known as Hera-II

and is even more impressive is

Hera-I which is unusual in that is has a row of columns down the centre – perhaps to support parts of the structure, or to divide its use into two parts or to create a sense of

symmetry which was very important in building design of this period and some interesting tricks (such as subtly varying pillar size or wall thickness) were often used to solve design or location problems in order to ensure that the symmetry rules were followed. Symmetry rules also apply to statues but we have not seen that in practice yet.

Worshipers at the temple were often seeking help from the Gods and Votives such as those above were left by them at the temple. These seem to have been somewhat unceremoniously cleared into a large pit near the temple from time to time and covered over.

There are numerous houses around the site and one of them clearly shows the Roman techniques of wall construction (aka Opus).

Here the regular end sections are infilled with Opus reticulatum dating from the 1st C BC. Click here for a good explanation of the varieties.

Doorways showed how the doors themselves worked with

hinge post holes (top right of the doorway) evident at the base (we are to see actual doors dating from this period later on apparently).

As a start to understanding the design and function of houses, we got the chance to walk around a mid-size house - not a villa since villas were built outside of the city walls and a domus (house) was built inside the walls.

The floor in this section was relatively plain indicating the the walls were probably highly decorated – Romans

tended to have great floor or great wall decorations in a room but not both.

The inner courtyard was surrounded by a pillar supported roof allowing rain to enter through the middle. Water is then usually collected in an underground cistern for later reuse.

(As an aside, tour groups have to have an official Italian State Registered guide on sites – we had one and here she is seen sitting down and listening to our group guide who was with us the whole week and was extremely knowledgeable and patient with our simple questions)

Some pillars were solid stone but the majority were constructed from shaped bricks

and then rendered and plastered with moulded stucco (or covered in mosaic).

There is a good 3-D walk around of a Roman Domus here which gives a feel of what we would have seen when houses like this were built.

An oddity in the site was a building thought to be a buried

tomb. The roof tiles on it are the originals

and found inside the tomb were 6 ornate vases with the

most amazingly detailed handles – quite something for craftsmanship 2000 years old.

One structure on site has defied interpretation – it seemed to have been filled with water, a ramp at the far end and

possibly wooden platform base at the end closest in this photograph. The ramp would not have been used for disabled access so we wondered if it was used to drive cattle in for washing before sacrifice.

The site museum is really very good and has within it, some examples of tombs found outside of the city. The pièce de résistance is “The Tomb of the Diver”

diagrammatically shown above

and now shown in its real sections.

It has the most amazing and vivid colours and we found that binoculars were very useful for looking at the detail since you are kept some distance from it in the museum.

Each picture tells a story or is evidence of the customs of life. More information and links about “The Diver” can be found here.

Tombs were decorated on the inside with Frescoes painted onto fresh lime render on large limestone slabs.

|  |

Other examples of the brilliance of the frescoes include:

|  |

here the deceased is shown laid out with mourners tearing their hair out in grief,

here we have the Ferryman Charon crossing the River Styx,

a detail from the top right hand corner of the previous fresco possibly showing distress about the departed

and presumably a scene from chariot racing whilst alive. The paintings themselves give historians a good idea about chariot design and construction.

You were not allowed to be buried inside of the city walls so if you were wealthy usually your ashes were put inside a tomb (burial did not become common until towards the end of the Roman period). If you were poor, you were just dumped in a common pit!

The museum also has on display some amazing examples of decorated pottery found on the site.

These had some of the most delicate decorations we have

ever seen. Here is part of a very large vase

a fish plate

and to finish, a pair of pipes of the type often seen in frescoes. All in all, a great first day.

No comments:

Post a Comment